Frank Miller is a tough guy to do a top 10 for. His early comic book career changed superheroics forever—and that was way back in the early 1980s at Marvel, and then the mid-’80s at DC. His indie career, beginning in the early 1990s, paved the way for the neo-realistic post-noir comics that literally wallpapered the racks by the year 2000.

And then he turned to “historical fiction” and, once again, created market where there really hadn’t been one before. Along the way, he experimented with publication formats (higher-quality gloss with longer page counts in Ronin and The Dark Knight Returns; wide-panel hardcovers with The 300; pulpy B&Ws with Sin City), shattered all genres, and crashed into screenwriting with original scripts for Robocop 2 (deemed too violent to film) and adaptations of his own original work that proved hugely successful, as well as inspiring the modern superhero film with his work on Batman.

He was controversial as Hell, with his use of graphic, detailed, physical violence and his seeming glorification of vigilantism in a much more realistic, street-focused way than ever had been done before.

So when you pick just ten great Miller books, do you go for breadth? Do you go for sales numbers, influence, or critical success? I don’t know if there’s a “right” answer to those questions, but I can tell you what I chose to do: I’m picking the ten I enjoyed reading the most. The ones I can pick up over and over, and/or the ones that influenced the way I buy and read comics.

THE BERKELEY PLACE TOP 10 FRANK MILLER COMICS

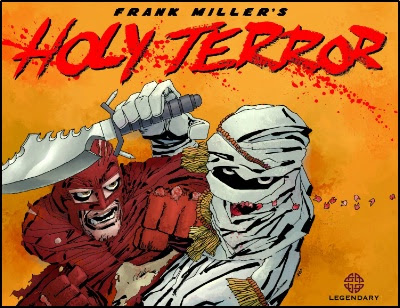

10. Holy Terror (2011)

Miller’s Batman-versus-Bin Laden story, which was rejected by DC and ultimately published as a hardcover graphic novel by Legendary Comics.

The book is told in Miller’s The Dark Knight Returns style, down to the design and movements of a “Robin” character. It is a relatively short and simple work. But the pacing is perfect and the art is classic Frank Miller. Every comic book critic gets to put their own “wild card” on lists like this, and this one is mine.

9. Elektra: Assassin #1-8 (1986)

As you read this list, you may get the sense that everything Miller did in the 1980s got nominated for awards. You’d pretty much be right. But this book was especially worthy.

With representational watercolor art by the great Bill Sienkiewicz, this book was Miller’s statement about his own work on Daredevil. It was too violent to get comic code approval, and the illustrations were too graphic for underage readers, so it was published as part of Marvel’s short-lived “Epic” line of more adult-oriented series, printed on higher quality paper. The book almost seemed to be satire in the way it handled standard Marvel tropes like ninjas and SHIELD, and doesn’t appear to fit in standard Marvel chronology.

According to Wiki, it does fit because Garth Ennis wrote about the events described in this series during his Punisher run—but Ennis’ Punisher run also seems to be non-canonical.

Ultimately, it doesn’t matter. The fact that Marvel published this book shows either that they had no idea that Miller was actually making fun of them through his over-the-top excess, or it means Marvel is fine with teasing. As long it sells.

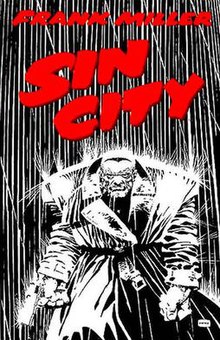

8. Sin City: A Dame to Kill For #1-6 (1993)

The first in his Eisner- and Harvey-winning Sin City series is still in my view the best, because it represented such a deparature from most crime comics but also because graphically it was the logical progression of this artist from the restrictions of Big Two comics. I’m not as big a fan as Sin City as many are, but I can appreciate its power and influence particularly in this first arc.

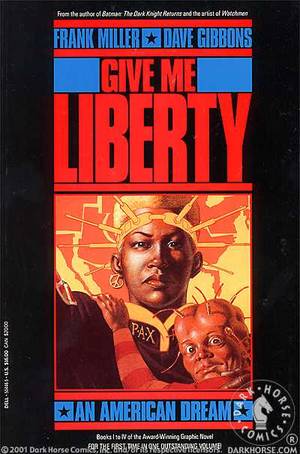

7. Give Me Liberty #1-4 (1990)

Frank Miller and Dave Gibbons create an African American female in a dystopian future in this Eisner-winning project. I think the book seems a little dated by today’s standards, but at the time “dystopian futures” with political overtones were still a relatively unexplored genre.

Subsequent Martha Washington stories decreased in quality quickly, but this one won the Eisner in 1991.

6. Ronin #1-6 (1983)

Ronin was a DC comic that had nothing to do with the DC Universe. Not a passing nod, no attempt to describe an alternate Earth. It’s never been “folded into” the DCU, either, as DC did with Wildstorm and many Vertigo books. It predates Vertigo in fact—as did Watchmen—but the critical success of this book was partly the inspiration for DC to have a creator-owned imprint.

Before Ronin, DC had experimented with the glossy-paper format with the extremely successful Brian Bolland series Camelot 3000 as a means to produce a DC comic (that had nothing to do with DC Comcs) by a well-established creator. 50 pages per issue, no ads.

And so was born a new format for comic books—one that Miller himself would build on in Dark Knight Returns, and Alan Moore would use to great advantage in Watchmen.

Lots of folks forget this book, but it really was the one that launched the beginning of a new format and publication structure of comic books.

Plus, it was artistically a home run: Ronin built on Miller’s manga-style, and represented his first collaboration with painter Lynn Varley. He had originally approached Marvel with the concept, but DC made him a better offer and so he went across the way to the “other big one,” in his first major break from Marvel.

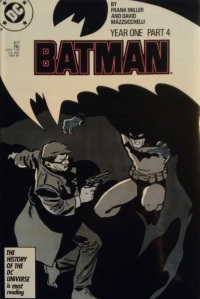

5. Batman: Year One (Batman #404-407) (1987)

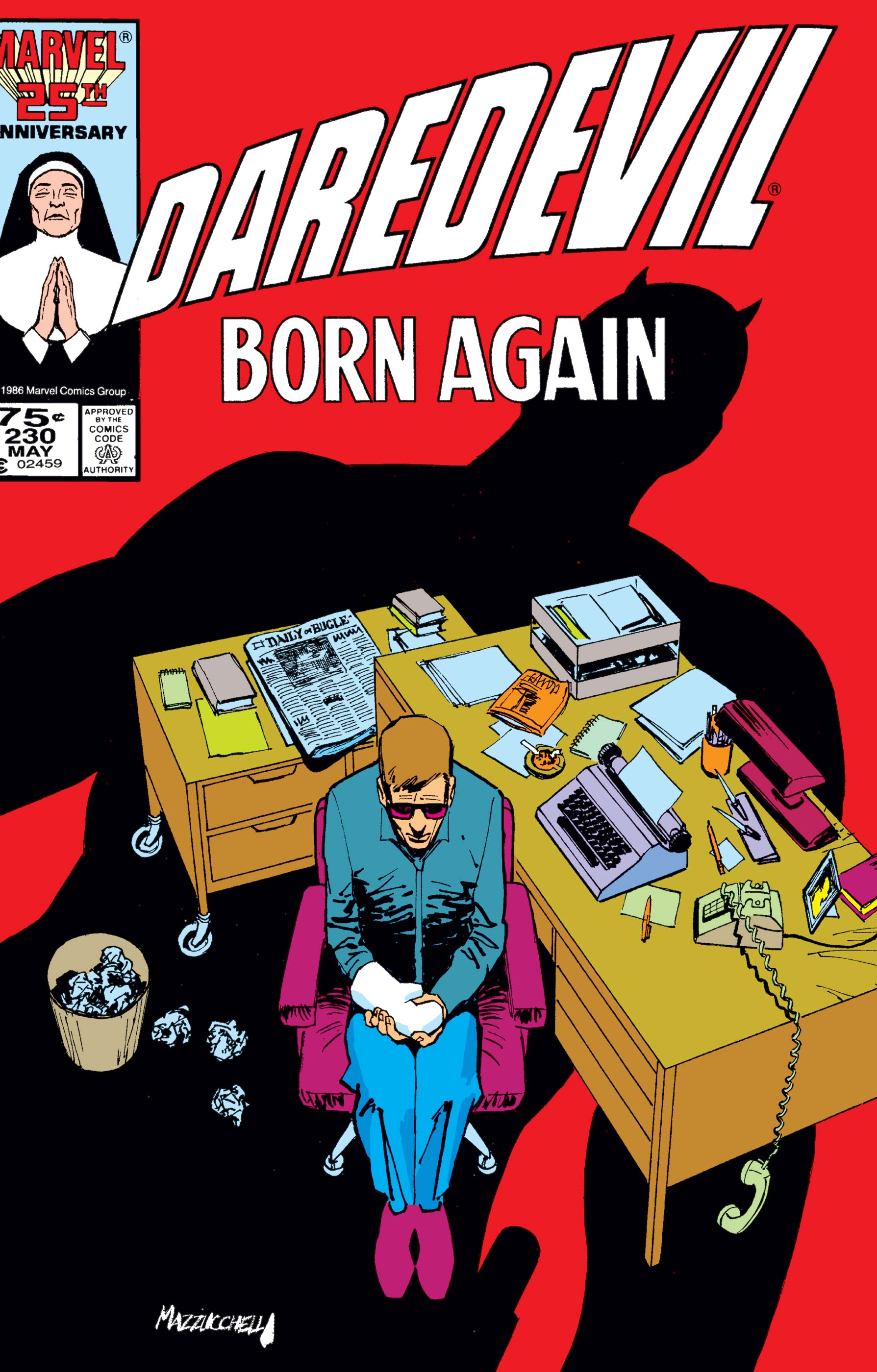

Miller and David Mazzucchelli join forces again, after having worked together on Daredevil Born Again (see #1, below), to tell the opposite story of The Dark Knight: Batman’s first adventure. Miller would explore the character’s roots again in All Star Batman and Robin, but this book is far and away a better, more influential title.

It was also the first “Year One” published by DC. Many more would follow. Some were very good. But none redefined the main character like this one did.

Once again, Miller broke ground that others would tread and retread for years—decades!—to come.

4. The Elektra Story (Daredevil #168-182, 189-190) (1981-82)

In Daredevil #168, Frank Miller created arguably the most important female comic book character of the 1980s: Elektra (misspelled “Elecktra” on the cover). As readers, though, we still didn’t know how important she’d be. Issue #169 focused on “crazy bullseye,” and then #s 170 to 176 focused on the “Kingpin Must Die” story, where we saw the characters competing for the role of lead assassin. In #179 the story deepened, and then in #181 we got the classic double-sized issue “One Wins, One Dies,” which was absolutely iconic. (It also made me some good money—I was smart enough to buy multiple copies when it came out.) Along the way, Miller also created The Hand. The resurrection of Elektra, in issue #190, was equally powerful—and served as the perfect coda for Frank Miller’s run.

Daredevil #182, though, is my personal favorite of the bunch. After the huge “event” of #181, which fans had been looking forward to for over a year, we got a quiet, mournful book about death and loss that showed that Frank Miller had a softer side, a human side. It’s what separates Daredevil from so many copycat books that followed it: The comic wasn’t just violent to sell books, it was violent with purpose, meaning and effect.

Miller’s slipping Elektra into Matt Murdock’s past, and his reexamination of the character’s roots, also helped along the “retconning” rage that would infect so many big two titles in the 1980s. Alan Moore—the other most important comic book guy of the 1980s—did it in Swamp Thing, but don’t forget about John Byrne’s renovation of Superman, Peter David’s Hulk, Mark Waid’s Flash work, Roger Stern and Byrne’s renovation of Captain America’s origin…It was almost as if Miller gave the industry permission to reexamine its roots. Incidentally, this sense of timelessness is what inspired the second entry on this list, The Dark Knight, which examined what would happen if Batman actually got old.

_1.jpg/250px-Wolverine_(vol._1)_1.jpg)

3. Wolverine #1-4 (1982)

Although Chris Claremont is credited as the writer of this series, in interviews he’s done since the book became the character-defining book of one of Marvel’s most lucrative characters, Claremont has credited much of the story and content to Frank Miller. Even putting Logan in Japan, and the line “I’m the best at what I do, but what I do best isn’t very nice,” come at least in part from Miller. The two creators came up with the concept during a long car ride together. Miller had earned his way into becoming one of the most important comic creators of the early 1980s (and was clearly on the way to being one of the most important of all time), and Claremont was easily the most influential writer of the late 1970s and early ‘80s, so it made sense for them to collaborate. All they needed was a project.

Miller’s artwork on this comic—Manga-inspired page layouts of combat sequences that felt more like moving pictures than comic frames—influenced generations to come, and represented the perfection of what he’d started with Daredevil.

The upcoming Wolverine movie is based on this miniseries.

2. Batman: The Dark Knight Returns #1-4 (1986)

When your only competition for the most influential book of the 1980s is Alan Moore and Dave Gibbons’ Watchmen, you know you’ve created a significant work of art. There may be disputes as to whether this book or Watchmen is the book that truly “changed everything” and made it okay for grown ups to read comic books, but who cares? This book was absolutely brilliant and, when it came out, I daresay that every comic fan who read it was changed forever. Some may hate how it moved the industry away from the “fun” of the early 1980s, some may argue that it was too dark to be considered a real superhero comic, but it doesn’t matter.

None can dispute the power it had not just in storytelling, but marketing and format—arriving as it did in four oversized issues with card-stock cover and colors, by Lynne Varley, that were unlike any anyone had ever seen before.

It also changed the legend of Batman, paving the way for the architecture of Grant Morrison and the films of Christopher Nolan. When this book came out, Bat-sales were low. Afterwards, Batman became—and continues to be—the most commercially lucrative comic book character in the world. It changed how DC looked at itself, too—finally giving it a basis to compete on a content-level with Marvel’s “realistic and relatable” approach to the art form. It won four Kirby Awards in 1986 and 1987 and then, ten years later, won a Harvey for best reprint project. It’s reputation has stayed in the forefront of the collective comicbook consciousness for over 30 years and shows no signs of fading.

Oh, and we finally saw who would win a fight between Batman and Superman. And true comic fans were not surprised by the answer.

1. Daredevil: Born Again (Daredevil #227-233) (1986)

It won two Kirby awards (for story and art), has been rumored to the be the basis for several attempted movie reboots of the character, and is still reprinted in many forms today—including a beautiful recent over-sized “artists edition.” This is the best Daredevil story ever because it captures all of the various elements of the character that were either introduced or capitalized on by Frank Miller during his legendary first run on DD. In addition, the “fall from and return to grace” story pattern—done here in just six issues—became the blueprint for the three major runs that followed: Brian Michael Bendis, Ed Brubaker and Andy Diggle. It’s the best Frank Miller story because it combines all the grit and violence that he’s best known for with a thoughtful look on how that neorealism should affect the Marvel Universe: By juxtaposing Nuke and Captain America. What do superheroes mean in a world that is as cynical as Stan Lee was cheerful? This is the answer.

Two thoughts: I will concede that “The Dark Knight Returns” was one of the most important comics of all time, because it put Batman back on the map, the same way that Adam West did two decades prior. Without Adam West and Frank Miller, ‘Batman’ would by now be just a curious footnote in the history of American popular culture. The reinvigoration of ‘Batman’ does seem to come in twenty year cycles. The importance of “The Dark Knight Returns” simply cannot be understated. Having acknowledged this, I am going to take the very unpopular position of saying……… I wasn’t crazy over it, either then, or now. The story of an aging Batman coming out of retirement to save his city one more time was awesome, but this miniseries had too many elements I did not care for, most significantly, the artwork. Now, maybe a good argument can be made that Miller’s relatively crude art-style was a good compliment for the politics of this tale, but I love comics, and you’re going to catch me reading a good comic-book six days out of the week as opposed to reading Robert Louis Stevenson or Alexandre Dumas, simply because the frustrated cinematographer in me loves great action artwork of the Byrne/Adams/Colan/Perez/Kubert variety, and Frank Miller’s style-especially on this particular project- just struck me as crude and even rushed, in comparison with those aforementioned titans. I found the character of Carrie Kelley to be trite and unnecessary, which is how I feel about ALL post-Dick Grayson Robins. Seriously, Bruce- a pre-teenaged girl as an urban crime-fighter??? Yeah, THAT’S gonna play out good!! WHAT could POSSIBLY go WRONG with THAT????!!!! Corporate mandates notwithstanding, bringing CHILDREN in to fight urban crime is unforgivably stupid. What happened to Jason Todd in “A Death in the Family” was, mathematically speaking, grossly overdue TO happen, but, to this day, Bruce Wayne simply has not learned his lesson! What is taking Bruce Wayne so long to be indicted for gross child-endangerment??? If Warner Brothers feels like Batman absolutely MUST have a “Boy Wonder”, then why not develop the ONLY “Dynamic Duo” that makes any logical sense, namely, Batman and Nightwing-??? Nightwing is a great character- a golden example of the student surpassing the Master, and, arguably, even a more interesting character overall. They don’t have to work together every single issue- just often enough to satisfy Warner Brother’s “Dynamic Duo” mandate, just like they did throughout the 1970’s! ( aka the “Wayne Foundation Building” years ) Dick Grayson/Robin/Nightwing possesses a truly staggering propensity for survival and loyalty to Batman and his cause that I truly believe is lacking in most, if not all, his successors, a fact of which Wayne lost sight of somewhere around the time of the murders of Joe and Trina Todd. Robin fucked up here, all right, but to “fire” an otherwise perfect partner-in-peril over the matter was a serious breakdown of judgement. I guess Batman doesn’t think something like that could happen to HIM. ( right ) So, “The Dark Knight Returns” sets the “revolving Robins” concept in cement, and crude-to-poor artwork is celebrated as “groundbreaking”, and Batman kicks Superman’s ass. Let me clarify this final point for anyone who requires it: Batman could NOT defeat Superman even on his BEST day, and Superman’s WORST- not even with all the Kryptonite on Earth! Nossir!! Any perception to the contrary is a FANTASY. The Man of Tomorrow is, for all intents and purposes, a GOD, his natural modesty notwithstanding, and no fat, washed-up, played-out, middle-aged billionaire vigilante is going to knock him off! The Man of Steel is just too smart for that. This is not to say that Batman could not possibly succeed in luring him into some kind of a Kryptonite-laden death-trap, but that’s GUILE, not overwhelming physical might. So- those are my thoughts on “The Dark Knight Returns”. My SECOND point in this overview of Frank Miller’s career is Mr. Ekko’s assertion that Elektra Natchios is the most important female comics character of the 1980’s. Wrong-O!!! THAT illustrious honor goes to the Phoenix, who mostly existed from 1976 to 1980, but, nevertheless, her most important impact played out across the first two-thirds of 1980, culminating in her/it’s necessary destruction at the conclusion of the “Dark Phoenix Saga”. The repercussions of the tragedy of the “Dark Phoenix Saga” are still being felt to this very day, and will undoubtedly continue to do so for many more years, if not decades, to come. Coming in at a VERY close second place is Storm. Storm singlehandedly redefined superheroinism. Storm is to superheroines what Beyonce is to pop music. She is the DEFINITIVE superheroine, and even though I generally don’t enjoy supercharacters who are flawless in every single way, the beautiful Storm is the X-ception to my rule. She checks all the boxes!! The Scarlet Witch is neurotic, of course, the Invisible Woman’s heart isn’t into it, the Wasp is ( slightly ) flaky, ( I suspect at least SOME of that is an act ) Wonder Woman and the She-Hulk are ( slightly ) arrogant, ( NOT an act ) the Black Widow is of somewhat-questionable morality, and so on, and so forth. But Storm is an absolutely flawless product of nature, and her power, sense of loyalty and justice, and, well, godliness, all combine to make her the Super-Deal, thus she is the Number Two Most Important Female Character of the 1980’s! ( of course, if it can be determined that the Phoenix-entity is either actually male, or at least gender-neutral, then, obviously, that would take our Miss Ororo up to the top-slot! Maybe time will tell!! X-celsior!!! )

I never thought about comparing Dark Knight to Adam West’s Batman…But you’re right. The Batman tv show was also important because it moved the idea of comic books out of kiddie racks and into colleges. Dark Knight also became college-level reading.

I take and concede your point about there being other more important characters than elektra in the ’80s, especially as to Jean Grey, but I still think Elektra did things that those others did not. She rode a line between good and evil, and was a stone cold killer. Black Widow should have been able to do the same thing, but really has rarely been portrayed that way–and certainly not in the ’80s.

Everybody knows that the character of Batman stands at six-foot-two. Here’s a little Bat-fact I picked up less than a week ago: The only actor ever to play the Dark Knight who actually reached the correct height requirement of 6’2″- that’s right, Adam West. As songster Wally Wingert put it in his 1990 tribute to the late actor, “Adam West”, “…….he’s got cool, and savoir-faire, in his cape, and his cowl, and his gray underwear! Who’s the superhero that we like best??? If you’re gonna be the Batman, you’ve gotta be Adam West!!!/ …….I’ll be at home watching Batman, Batman, starring ADAM WEST!!!!!!!!!” Bigod!!!!