Note: I am reprinting, without change, a series on Grant Morrison’s Batman work originally printed in 2013 on my old site.

Today’s post will be broken up into a discussion of three issues of Batman that occur after the “Batman and Son” arc, but which seem in some ways to be disconnected: Batman #664-665

After completely rocking our world with his first major story arc, in which Grant Morrison introduced Batman’s son (or at least brought Damian into the “canon” DC Universe) and began hinting that Batman is actually insane, Morrison seems to return to a somewhat more standard story: Bruce Wayne catting around and Batman doing detective work. I say seems to because with Morrison, nothing is every insignificant.

*Note: I’m skipping over a one-shot, illustrated story called “The Clown at Midnight,” because it doesn’t really affect the major Morrison Batverse.

THE THREE GHOSTS OF BATMAN (Batman #664)

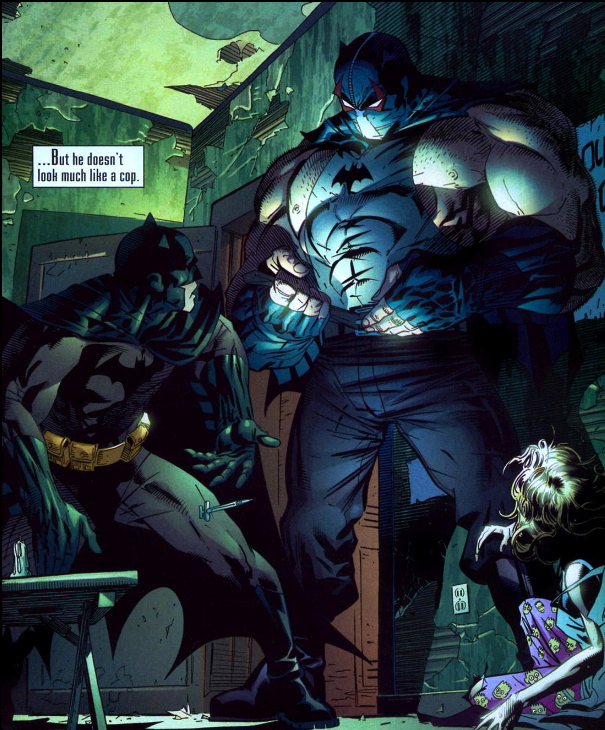

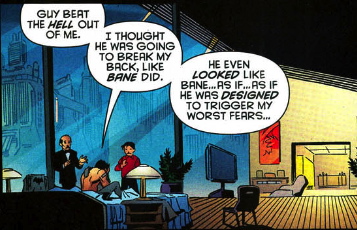

As we discussed, in his first issue of Batman and Son Grant Morrison showed us two other Batmans, and hinted that they had some kind of relationship to Gotham’s police force. We are introduced to the third “ghost of Batman” halfway through issue #663. And he looks an awful lot like Bane.

Batman even recognizes the similarity.

We meet Bat-Bane when he’s getting hookers delivered to his lair, where he literally tears them apart and leaves them lying around among other “take out” remnants like pizza boxes. Like the original Bane, Bat-Bane almost kills Batman.

THE BLACK CASEBOOK (#665)

The Black Casebook is sort of Batman’s X-Files….

DC has since reprinted the wild, fanciful stories that “couldn’t be explained” by present Batman canon, and titled it, of course, The Black Casebook.

The story itself is the second half of Batman vs. Bane-Bat, and it’s a solid comic book fight story. Morrison is letting us rest a little bit here from having to dig into arcana and pay minute attention to everything that happens. I’m sure it was intentional, on his part, to use an extended fight scene as a rest break.

Andy Kubert shines here, but we also see that comic book fight scenes don’t have to be boring. Morrison and Kubert do a lot to develop Batman’s relationship with Tim, the “real Robin,” who is insecure after having been beaten by a nine-year-old so handily.

Towards the end of the second issue of this arc, we see The Black Glove for the first time—just the gloves, spying on Bruce and Jezebel Jet. It’s the first inkling we have that someone other than Talia knows Bruce’s secret and is going after him both as Batman and Bruce. It’s also an example of how patient Morrison is. The Black Glove won’t materialize as a true threat for over a year’s worth of comic books…

Oh, and look closely at the Zurr En Arrh graffiti on the wall behind Bat-Bane in this issue and the next. Because it appears and disappears based on whether Batman is conscious enough to read it. These are the seeds of his insanity, and clearly show that The Black Glove has created a chemical trigger for the post-hypnotic suggestion: When Batman is around the “ghosts,” they emit a gas that begins to trigger Batman’s inability to tell what is real from what is not.

THE LEGEND OF THE BATMAN: WHO HE IS AND HOW HE CAME TO BE (Batman #666)

The third and final story we’ll examine today is perhaps my single favorite Grant Morrison issue of all time.

It appears at first blush to be a done-in-one vision of what it would be like if Damian Wayne became Batman in the future (and if Barbara Gordon led the Gotham City Police Dept.). But there is so much more going on here.

First, in his “origin,” we see Damian crying over the bloody body of the original Batman.

The picture is reminiscent of a panel from Batman & Son (in issue #658) in which Batman appears over Tim Drake’s body after he was beaten by Damian. It also looks a lot like most drawings of young Bruce Wayne over the body of his parents.

From there, this tale becomes deceptively simple and incredibly rich. First of all, there’s the casual reference to WB Yeat’s work during his “Celtic Twilight” period, in which the poet focused on traditional meter and structure in a response to more modern poetry that eschewed formal structure. This, of course, is what Morrison has done for this arc. In Batman & Son, he played with the concept of comic books and pop art and his artist used unconventional panel arrangements, often busting out of the panels themselves. There is much less of that in this story, and the two issues before it, which hew closer to a traditional “Batman” story.

We also get so see that someone named “Professor Pyg” is a major crimelord in Gotham’s future. But we won’t really get to know this character (or even see him again) until Batman & Robin #3, many years later and long after many readers have forgotten this story.

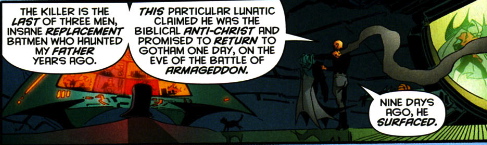

We also learn that although Batman beat the first two Ghosts of the Batman in the previous issues, the third survives into the future to become another major player on the crime scene: A sort of “Punisher” version of Batman, whose goal is to destroy all criminals and rich people alike, and bring hell on Earth to the people of Gotham. We’re told by Damian that the ghost is “the last of three men, insane replacement Batmen who haunted my father years ago.” This is another piece of the puzzle that hasn’t been quite so clear before. Finally, Damian refers to Lane as the “son of Satan,” implying that Lane’s creator is the father of the ultimate evil. Damian states that he took on the cowl in a deal with the Devil, “in return for my soul,” suggesting that Damian knew Lane’s creator and that that creator had something to do with Damian’s own creation. We will learn later how true all of that it.

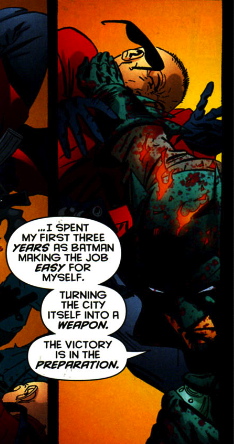

And Morrison builds into his characterization of Batman a recognition of Frank Miller’s seminal work on The Dark Knight, another future tale of Batman—but a future that comes out very, very differently. In that book, Miller establishes that Batman is the most powerful hero not because he’s “super” but because he plans, plans, plans for every outcome.

But is Morrison also suggesting that DC is preparing for the future of Batman by allowing Morrison to write this story? Is this canon? Is this inevitable?

Probably not. Brilliant as he is, DC is a corporate comic book company and is unlikely to allow a single comic to control the future of its most commercial property. Plus, the new 52 completely undermined Morrison’s work.

But Goddamn it’s cool.

And there are other indications in the book that suggest it may indeed by canon: The three Batman and Robin costumes that Damian has set up in the Batcave look exactly like Dick-as-Batman, Tim, and Damian working together, which happens later in the DCU both in the Grant Morrison epic (in the pages of Batman & Robin) and in the related Batbooks.

Next: Club of Heroes!